Lockdown: invisible eyes

Last year a Chicago gent by the name of Fidencio Sanchez made the news by selling frozen juice bars—paletas—from his hand-pushed cart at the age of 89.

His story, and the story of the Wisconsin restaurateur who thought Sr. Sanchez ought to be enjoying his retirement, is here.

In the late nineties, my friend Lia Matera asked for a short story for her collection, Irreconcilable Differences. I was living in Watsonville at the time, where ice cream vendors were more likely to be behind a push-cart than behind a wheel. These guys are part of the scenery: they go all over, talk to everyone, see everything…

And a lot of them are old—like Tío, the protagonist of “Paleta Man” (which went on to an Edgar nomination). Tío—which means uncle, and is often used as an honorific—has a lot more history than just as a seller of sweet ices.

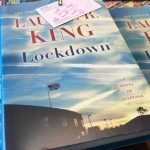

That made him one of the building blocks for Lockdown, the story of how the lives of a community come together, for better and for worse.

5:52 am, Career Day

Tío

Jaime Ygnacio Rivera Cruz—Tío to the residents of San Felipe and the students of Guadalupe Middle School—watched yesterday’s coffee rise up the woven threads of his clean rag. He squeezed it, then slid his left hand into the shoe and began to rub the damp cloth around and around, his father’s trick to bring up a gleam on aged leather.

Perhaps it was time to buy a new pair. He had money now, more than he could have anticipated just a short time ago . . .

But discarding these would feel like an admission of defeat. And Señora Rodriguez had told him of a reliable shoe repair shop, at the other end of the county. He had doubts: this was not a generation of repairers. Still, he had bought these shoes for his wedding. They were on his feet the proud day he was hired for his first real job, and on the Sunday morning his son was baptized. He had worn them on the rainy afternoon that son was lowered into a hastily dug grave, and again two weeks later when his wife was buried at the boy’s side. The shoes had gone with Tío across the border and through the desert to America, many years ago. Old comrades, who deserved preservation.

When the shine was to his satisfaction, he set them aside, washed his hands, and finished dressing. The rest of his clothing was equally respectable: the brown janitor’s shirt was freshly ironed, as were the trousers, every button and fold in place. No necktie, though. Tío still did not feel properly dressed without a necktie, but appearance was all, especially when it came to the fragile sensibilities of adolescents.

His first day at Guadalupe, he had worn a tie and the students had mocked it. The second day, he had let his collar go bare for the sake of invisibility. The tie would remain in the drawer until such a time that he could reclaim his dignity.

He studied his reflection in the cracked mirror. Of the many faces he had worn in his life, this one might be the most deceptive. And to think how terrified he had been of the uniform—of the very idea of setting foot onto school grounds. How close he had come to turning the job down untried.

Little did he anticipate the doors that would open to a lowly school custodian. Limpiador simply meant one who cleaned, but his old English dictionary told him that janitor had to do with doors. The janitor was a doorkeeper. And the word custodian? In either tongue, that had to do with custody, with possession. With guarding.

The word made him the possessor of Guadalupe Middle School and all its persons. To guard the place as he saw fit. Children might disappear, boys might shoot each other over drugs, but not while they were at his school.

And surely the triangle of crisp white undershirt at the neck bore the same function as a necktie?

Yes: on such a day as this, it was better to show the uniform than the man inside.

Perhaps, however, not when it came to young Mr. Santiago Cabrera—who called himself “Chaco” as an emulation of his dan- gerous cousin, the man with dreams of drug cartels in his heart. Chaco Cabrera needed to see past the surface of his school’s janitor, just a little.

Because Tío had plans for Chaco. Plans that did not include permitting the boy to follow his gang-banger cousin “Taco” into a courtroom on a charge of murder.

Lockdown goes on sale June 13, but you can pre-order a copy from: Bookshop Santa Cruz (signed), Poisoned Pen (signed), your local Indie, Barnes & Noble, or Amazon.

Dear Laurie,

I am going through a very bad time financially right now at the age of 70. Your story about Tio come along at the best time for me. Thank you so much for all that you do.