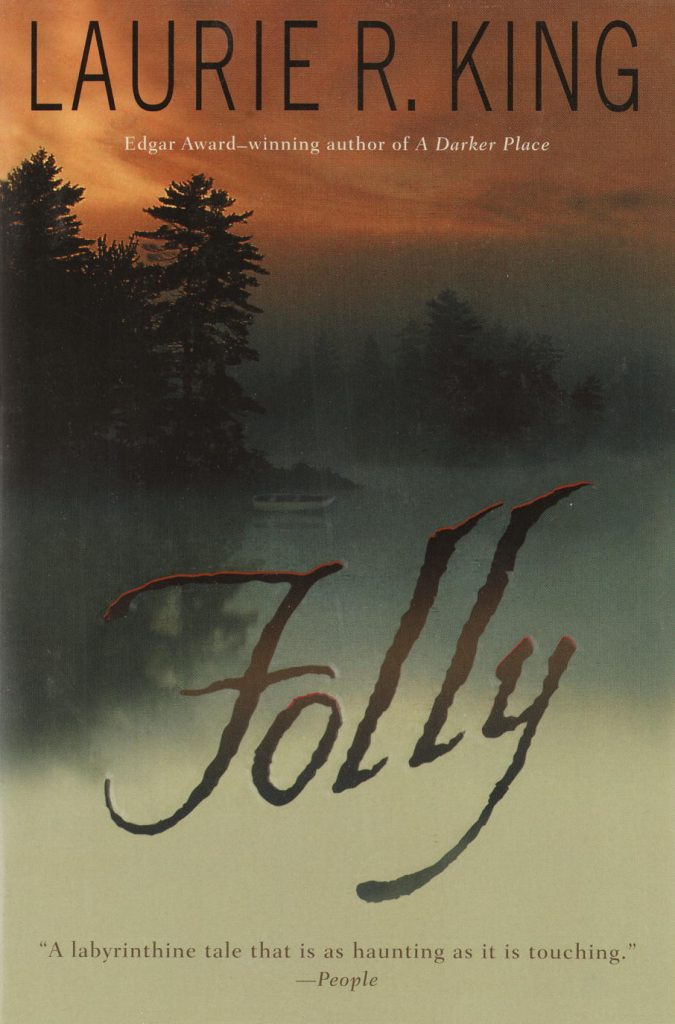

Folly

Buy the Book:

Buy the Book: Bookshop Santa Cruz (Signed)

Bookshop.org

Barnes & Noble

Amazon

Amazon UK

Audible

Libro.FM

Series: Standalone Novels

Published by: Bantam Books

Release Date: 2002

Pages: 432

Overview

What happens if your worst fears aren't all in your mind?

Rae Newborn is a woman on the edge: on the edge of sanity, on the edge of tragedy, and now on the edge of the world. She has moved to an island at the far reaches of the continent to restore the house of an equally haunted figure, her mysterious great-uncle; but as her life begins to rebuild itself along with the house, his story starts to wrap around hers. Powerful forces are stirring, but Rae cannot see where her reality leaves off and his fate begins.

Fifty-two years old, Rae must battle the feelings that have long tormented her—panic, melancholy, and a skin-crawling sense of watchers behind the trees. Before she came here, she believed that most of the things she feared existed only in her mind. And who can say, as disturbing incidents multiply, if any of the watchers on Folly Island might be real? Is Rae paranoid, as her family and the police believe, or is the threat real? Is the island alive with promise—or with dangers?

Discussion Guide

Download the Folly discussion guide

Praise

"Acclaimed mystery writer King has crafted a labyrinthian tale that is as haunting as it is touching. As Rae pieces together her house and her psyche, she slowly uncovers an extraordinary level of strength and tranquility. Solitude, broken up by some fun visits from a concerned and handsome local, is rarely this enticing."

—People Magazine, a “pick”

"Rae’s quest [to rebuild Folly, her great-uncle’s home, and possibly her shattered life] is the absorbing subject of Laurie R. King’s Folly, a deeply involving novel that’s moving and disturbing. King constructs a sturdy foundation on Gothic elements and uses them to explore the effects of mental illness and steadily build an unnerving creepiness."

—Miami Herald

Links

Read Laurie's thoughts on writing Folly on her blog, Mutterings.

To look at the San Juan Islands or to watch for Rae, Allen, Jerry, or Ed.

Excerpt

Folly (from OF, fol, fool):

1. lack of good sense or normal prudence and foresight

2. a foolish act or idea

3. evil, wickedness; criminally or tragically foolish actions or conduct

4. an excessively costly or unprofitable undertaking

5. an often extravagant picturesque building erected to suit a fanciful taste

(from Webster’s Ninth New Collegiate Dictionary)

Preface

The gray-haired woman stood with her boots planted on the rocky promontory, and watched what was left of her family pull away. The Orca Queen’s engines deepened as the boat cleared the cove entrance, and its nose swung around, a magnet oriented toward civilization.

Go, she told them silently. Don’t slow down, don’t even look back, just leave.

But then Petra’s jacketed arm shot out from the boat’s cabin, drab and shapeless and waving a wild adolescent farewell. Rae’s own hand came up in an involuntary response, to wave her own good-bye — except that in the air, her wave changed, the hand reaching forward, stretched out in protest and cry for help, as if her outstretched fingers could pull them back to her, as if she was about to take off down the beach, scrambling desperately over rocks and water to call and scream and —. She caught the gesture before any of the three people on the boat could see it, snapping the offending arm down to her side and standing at rigid attention. The boat dwindled, rounded the end of the island, and was gone.

Thank God they didn’t see that, Rae thought. The last thing I want is for Tamara to think I doubt what I’m doing. So why do I feel like some ancient grandmother in one of those harsh nomadic tribes, left behind on the icy steppes for the good of the group? I chose this. I wanted this.

The growl of the engines softened with the distance, grew faint, then merged into the island hush. No low mutter of far-away traffic, no neighbor’s dogs and children, not even the pound of surf in this protected sea. A small airplane off to the north; the rusty-wheel squeak of some nearby bird; the patter of tiny waves; and silence.

Alone, at last. For better or for worse.

Silence, and solitude.

Silence was not an absence of noise, it was an actual thing, a creature with weight and bulk. The stillness felt her presence and gathered close against her, slowly at first but inexorably, until Rae found herself bracing her knees and swaying with the burden. It felt like a shroud, like the sodden sheets they used to bind around out-of-control mental patients. She stood alone on the shore, head bowed, as if the gray sky had opened to give forth a viscous and invisible stream of quiet. It poured across her scalp and down her skin, pooling around her feet, spreading across the rocks and the bleached driftwood, oozing its way into the salt-stunted weeds farther up the bank and the shrubs with their traces of spring green, then fingering the shaggy trunks of the fragrant cedars and bright madrones until it reached the derelict foundation on which fifty-two year-old Rae Newborn would build her house, that brush-deep, moss-soft, foursquare, twin-towered stone skeleton that had held out against storm and fire and the thin ravages of time, waiting seventy years for this woman to raise its walls again.

Or not. This could easily prove a farce, a tragic folly demanding the effort and expense of a moon shot without a board ever going up. That garish blue tarpaulin covering her pricey lumber might prove her memorial, and Folly would have another chapter added to its already colorful history. Rae found that her right hand had wrapped itself around the opposite wrist, its thumb tracing the criss-crossed scars on the tender and vulnerable skin. She tipped her palms back and let the sleeves fall away, and studied closely the raised lines as if a message might be read there. One pair of scars had lived on her wrists for thirty years, but she could still recall the rich well of blood, the overwhelming feeling of relief, and the astonishing absence of pain. The slightly longer pair that overlaid them were ten years younger, not much pinker, and less clear in her mind. But on top of them, the most recent cuts were still bright and sharp. Almost exactly a year old, those.

The scars held a macabre fascination, even during those blessedly long periods in her life when Rae had no desire to add to them. The intriguing dichotomy of the toughness of human skin and its defenseless parting, the body’s grim determination to heal itself, the physical proof of how painful life could become, all drew her gaze. Most of all, though, she was constantly astonished — and even more, grateful — that in all that self-mutilation, she’d never managed to slice through anything essential to the working of the hand.

Perhaps there was a message to be read on the skin: Next time, use the gun, stupid.

At that reminder, Rae dropped her hands and raised her eyes to the campsite, searching for the green knapsack that held, among her other most secret and treasured possessions, the wood-grip revolver which had been the reason for her recent long drive up the coast: As Tamara had said, a plane flight would have been easier on everyone else — but they don’t allow guns on a plane.

She spotted the lump of green nylon on top of the heap of possessions that had come with her on the Orca Queen out of Friday Harbor, piled there by Petra and Tamara and Ed De la Torre, left for Rae to sort and arrange. In those haphazardly stacked boxes were tools and toilet paper, canned goods and dry socks, everything a marooned sailor — or woodworker — could ask for. At least the tarp that protected them from the drizzle, strung between tent and trees as an impromptu outdoor room, was a dull and inoffensive brown.

Rae’s gaze continued on, travelling from the shiny new camp equipment arranged at one side of the clearing to the two stone towers struggling out of the vegetation two hundred yards away. The towers were the only visible parts of what had once been a house, and they seemed to tug at her mind and at her hands, willing her to draw near. A house is an exercise in controlled tension, she mused. Who had said that? Whoever it was, they’d slightly missed the point: A house, she reflected, is more an exercise in using tension to control compression. It’s not tension that needs controlling, lest it pull a house to pieces, but gravity that threatens to push a building apart, its compression buckling walls and cracking foundations. Without the tension of a structure’s key elements — collar ties to keep the roof rafters from splaying, floor joists to transfer the compression of sofas and grand pianos and running children and lovemaking couples into the tension along its lower edge — the house curls up in a heap and dies.

The Hunter must have come up with that idea of house as a symbol of controlled tension, Rae decided. The succinct but inaccurate phrase had all the earmarks of one of the woman’s psychiatric aphorisms, applying the gravity of a thoughtful statement to counteract the stresses threatening to pull a patient to bits. Rae herself would have put it, A house is an illustration of the power of tension. Take a saw to the bottom edges of that floor joist, remove the tension of stretched fibers below and leave only the compression of gravity above, and the piano or the sofa or the lovemaking couple drops through into the cellar.

The use of tension, after all, was precisely what Rae was doing here, on this last island before an international border, a fifty-two year-old woman with too much scar tissue and too long a history of psychiatric fragility, a mad woman with a canvas tent, a supply of food, a bag of pills that would stupefy half of Seattle, a huge tarpaulined heap of building materials, and one small boxed collection of simple hand tools with which to tame it. No assistance, no neighbors, no electricity. No telephone, to cry for help.

And a massive sodden blanket of solitude dropped across her shoulders, threatening to flatten her if she dared move. The Hunter called it depression and prescribed pills and talk. Rae thought of it as compression. Its huge weight had crushed a marriage, ruptured the relationship with a daughter, and accompanied her to the doors of death three times. Rae knew, in her bones and with forty years’ intimacy with clinical depression, that for her, the only way to counteract it was to use tension — psychic collar ties — to keep the weight of her life from splaying her out and collapsing her in a heap. Fear was the only tension powerful enough to counteract the weight of the illness: not happiness, not work, not even love, but fear confronted, fears real and imagined. It had been the pursuit of fear that brought her here, to the ends of the earth, where it was going to be easy, so infinitely easy, just to step off.

Here on the edge of the world, on a narrow precipice above the final abyss, Rae Newborn had come to make her halfhearted stand. No safety net, no other to take responsibility, just Rae and her ghosts and demons.

She had come here because she was tired, not of life itself, but of living between. She had come to a place whose very name was Folly, as a way of forcing the issue. Rae had come here to meet her fear, to welcome it, and, if possible, to use it. If that high-strung tension failed to balance the weight of life, if she was pulled to pieces or crushed flat, well, at least a decision would have been reached. The relief from the uncertainty would be considerable.

She hadn’t told Dr. Hunt any of this, of course. The Hunter had problems enough with Rae’s loopy self-diagnosis and had vehemently disapproved of her patient’s self-prescribed plan of treatment, which amounted to recovery through hard labor. After all, Rae had entered the hospital in a state so low that she’d had actually to improve before she could attempt suicide. And although Dr Hunt had seen the symbol of house building (when it appeared in Rae’s therapeutic sessions halfway through the year of her hospitalization) as a sign of great hope, when it had dawned on the good doctor that Rae intended an actual, physical act of construction, she had been, professionally speaking, appalled. Was this not just another attempt at suicide, a substitution of lumber on a lonely hillside for sharp blades in the bath?

Rae did not argue with The Hunter. How could she? At the same time, once the hospital staff agreed that she was no longer a danger to herself or to others, neither did Rae back down from her decision. She waited out the remainder of the winter in the house of her combination nurse and babysitter, planning and gathering her strength. Then, when spring began, she packed her bags, ordered her lumber, arranged for her babysitter to drive her north, and prepared to step into the renovation process that a far different Rae Newborn had begun several years before. Although the process now had two enormous differences: She was on her own now, not one of a family of three; and in her knapsack she carried a gun.

A beautiful gun, with a worn wooden grip that endeared itself to Rae’s hand, as old as the hills but impeccably maintained, solid and efficient as its six trim bullets. Not that she would need more than one. Blades, she had decided, those exquisitely sharp and sophisticated scraps of steel that dominated her working life, did not belong here. Too, there would be no slow seeping out of life with a bullet. Final, like the solid slam of a well-hung door. The elegant old handgun lay in the bottom of the frayed knapsack that had belonged to Alan (and which still gave out the occasional grain of sand from one or another of the beach treks of his youth), wrapped inside one of Alan’s flannel shirts, nestled beneath a portable tape player (which the then eleven year-old Petra had produced when she had discovered that her grandmother was hearing voices) and a couple of paperbacks Rae didn’t know if she would ever get around to reading, under the leather-bound journal that was intended to be her substitute for psychiatric honesty, the white paper bag of substances that were intended to be her substitutes for psychiatric balance, and the plastic zip-bag of soil and ashes that contained the remnants of her life in California. On the very top of the knapsack’s contents rode her much-used carpenter’s apron, the leather tool belt that Alan had given her, half-joking, for their first anniversary nine years before.