The Business of Writing: Your Friend, The Agent

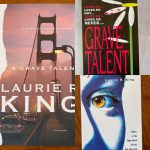

Part of the 30-year anniversary celebration of A Grave Talent.

Like most first novelists, I had no clue about how to run my life as a business.

In 1993, the only people who did self-publishing were the desperate souls who just HAD to have a volume to put in the hands of family and friends. The publishers who would do this for them were called “vanity” presses, which shows the scorn with which “real” published writers held them.

At the time, there were (as memory provides) only two actual, New York publishing houses that accepted manuscripts from the writer herself, rather than through an agent. These unsolicited manuscripts were called “over the transom” submissions, meaning that you had to (figuratively, at least) climb up and thrust your manuscript into the little window over their firmly shut door, listening to it thump down on the floor with a whole load of similar thick envelopes.

A junior editor described to me the way publishers dealt with them (those houses that didn’t automatically stamp them with RETURN TO SENDER.) Every few months, on a Friday night, the editorial assistants (all of whom wanted to grow up and become real editors with the budget to buy actual books) would send out for pizza and beer and sit around the storage closet with piles of thick manila envelopes, and start to read. Some manuscripts got a fair try, and got passed on to The Editor. Others would either have a typo that irritated the baby editor, or was not to their taste, or would have the bad luck to show up towards the end of the evening. Those rejects would be thrust back for RETURN TO SENDER with a printed “Thanks-but-no-thanks” slip. (Or just be tossed, to save the cost of postage, and “Oops sorry I guess we lost it.”)

Very occasionally, like the girl in the soda fountain who became a star, the stars would align, and the envelope would make its was to an Editor, who nine times out of ten would write a personalized “Good job, not for us” rejection note.

Very occasionally, like the girl in the soda fountain who became a star, the stars would align, and the envelope would make its was to an Editor, who nine times out of ten would write a personalized “Good job, not for us” rejection note.

Those that I sent in myself got rejected. Or “lost”…

…and THEN rejected. An agent was clearly the way to go. Agents held the key to that locked door. But how did I get one of them?

As I said in an interview a few years ago (2015)—

How did you get your first literary agent?

I looked in the back of Writer’s Market, back in 1987, and found five agencies in San Francisco. (I didn’t believe in New York. Still not too sure about it…) I wrote to each of them, sending a couple of chapters of the two books I’d finished. Agency one said their client list was full up. The second said they liked the one but not the other. Number three said they liked the other, but not the one. Number four said they’d be happy to read the books if I’d send them $385 for each. And the fifth was Linda Allen, who liked the books, thought they needed work, and ended up representing me until her retirement last year.

Or, as I put it in my Really Long Autobiography, Linda was—

The first professional to look at my work and see it as—well, my work.

She’s also been a friend all these years, although we didn’t really bond until she came to England for the 1995 Bouchercon in Nottingham, and stayed with us, visiting nearby Blenheim Palace

And venturing into cold, wet, windy Dartmoor, helping my two kids and me research The Moor.

(I nearly lost her in the fog, but fortunately, she heard me calling….)

She was a fairly new agency then herself, and the partnership went through some really great years, with this simple, small beginning.

She’s retired now, but I talked with her the other day, and she remembers how thrilled she was at the sale to St Martins Press.

And how much did I get from that first book? Well, more than the £25 Arthur Conan Doyle got for his first story, but in modern terms, maybe about the same. But hey, I was in business!

**

Read about A Grave Talent (with order links), see the other Martinellis,

or order a signed copy.

That is so cool!

I’m thankful that Ms. Allen was able to see the wonderful books in your manuscripts. I know my reading life would be missing something without them.

I was fortunate indeed.

Laurie

And of all things this made me remember was my elementary school way way WAY back when. There were transoms over all the classroom windows, and if you were favored, you got to close them at the end of the day with a very long (we were kids–tallness challenged) with a hook on the end that you had to get into the corresponding eye on the transom and push it shut.

(I like your books, too — see you at LCC, I hope)

I wanted transom windows at the upper reaches of my bedroom, and it took my contractor forever to find a classroom suppler who still manufactured them. And yes, I have one of those long poles with the hook to open their latches.

Laurie

I was amused at the observation that your first advance was probably no greater than the £25 that Doyle was paid for A Study in Scarlet, so I hesitated, but only briefly, to point out that he sold the rights for £25 while you presumably collected royalties after meeting that advance. Picky, I know, but I’d like to think that you found it profitable in more ways than one… A great book deserved a great reward.

Yes, in his case it was a payment, not an advance. At the time, he was happy to get it, but the publisher sure got a deal on it!

Laurie

I would love to know how much you changed Segregation in response to your agent.

In your place, I might have interpreted her suggestions to mean “removing the gradual evolution of her training with Holmes.” I would have missed that so much. I love the feeling of her wandering through her experiences with him, much as she wandered on the downs reading Virgil.

It must be very hard to figure out another’s suggestions when you are so close to the work.

I think I’ll do one of this month’s blog posts on the editorial process with Ruth!

Laurie