writing

Why we Love Publicity and Marketing

As we’re on the edge of being able to get our hands on an actual finished copy of The Lantern’s Dance (Feb 13) I thought this was a good time to look at one of the last pieces in the process of getting a book from the author’s mind to the reader’s eyes: Marketing and…

Read MoreAbsolutely the Final Draft(s)

Because what I do for a living often seems like magic—I come up with an idea and *SHAZAAM* the book’s in your hand—I’m writing a series of spoiler-free blog posts about the actual process. (Though rest assured—it’s still pretty magical.) ** “So, how many drafts do you write?” the question goes. Well, it depends on…

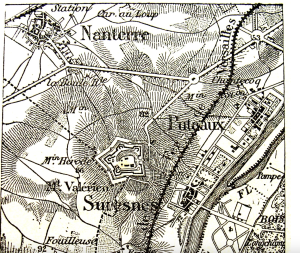

Read MoreResearching the Bits

This is one in a series of blog posts (without spoilers!) about the writing process for The Lantern’s Dance. Sometimes, I go into a book knowing a fair amount about the setting and situation. Other times, I just know enough to know it’s interesting—but there will be work involved to flesh it out. The Lantern’s…

Read MoreProof Positive

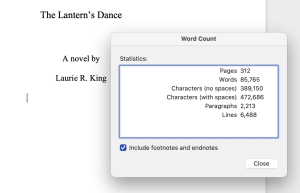

Because to the reader, a book goes from vague idea to hardback-in-hand, I’m doing a series of blog posts (no spoilers!) about the actual process for The Lantern’s Dance. (Though rest assured—it’s still pretty magical.) I’ve just finished the proof pages—those pages where the much-marked-up manuscript is formatted to look like the actual final hardback.…

Read MorePost-Final Drafts

This is one of a series of blog posts (no spoilers!) about the actual process of writing a book from the idea to the hardback in hand. In this case, the group effort behind the magic. I’ve talked about how The Lantern’s Dance began, and about the ongoing process of working with my editor,…

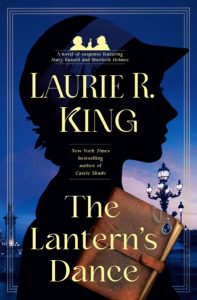

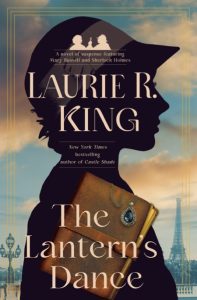

Read MoreNot Just a Pretty Face: Cover Art

(Because what I do for a living often seems like magic—I come up with an idea and *POOF* the book’s in your hand—I thought I might do a series of blog posts (no spoilers!) about the actual process. (Though rest assured—it’s still pretty magical.) In the publishing world, cover art comes before the book is…

Read MoreFeeling the Draft(s), First to Final

Because what I do for a living often seems like magic—I come up with an idea and *POOF* you have the book in your hand—I thought I might do a series of spoiler-free blog posts about the actual process. (Though rest assured—it’s still pretty magical.) April 1: first draft sent. (I talk about the earlier…

Read MoreWhat IS in a Name, Anyway?

Because what I do for a living often seems like magic—I come up with an idea and *POOF* you have the book in your hand—I thought I might do a series of blog posts about the actual process. (Though rest assured—it’s still pretty magical.) How do we writers name our babies? The ones on the…

Read MoreLantern’s Dance: The Beginning

Because what I do for a living often seems like magic—I come up with an idea and *POOF* you have the book in your hand—I thought I might do a series of (spoiler-free!) blog posts about the actual process. Though rest assured—it’s still pretty magical. As with many of my books, The Lantern’s Dance began…

Read MoreHitting “SEND”

I hit the SEND button–wahoo! First draft, hence short, untidy, and incomplete…but it’s sent, out into the editorial world. Now I wait, and see what she thinks. (*sound of chewing fingernails**) I think I’ll reward the newsletter subscribers with the first page this weekend. Or if not reward, at least give them something to talk…

Read More