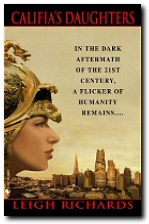

The Future (Califia’s Daughters 1)

I wrote Califia’s Daughters more than thirty years ago, but its meditations on the male/female relationships may be even more pertinent now than they were at the time. It’s a futuristic novel, although whether or not it is also dystopian depends on how you feel about today’s world.

Our future is both set in stone and malleable as wet clay: who we are now is a given; who we will become is an endless possibility. And although we assume that tomorrow will look much like today, change can accelerate, and catastrophes will happen. Novels of the future play at this meeting of set and soft. What happens if the ozone thins, if the planet warms, if a virus gets loose, if….

Over the next few days, I’ll be posting excerpts from Califia’s Daughters. Let me know what you think of them.

Califia’s Daughters (1)

By “Leigh Richards” (Laurie R. King )

Prologue

In the year 1532, Hernán Cortés sent an expedition west through Mexico to find a mysterious island which, rumor said, had brought huge wealth to the emperor Montezuma. When his man Mendoza came to the sea at last and gazed across the waters at what appeared to be an enormous offshore island, there was no doubt in his mind that this was the famed source of wealth. Nor did he doubt that this was also the land described by a Spanish novelist named Garcí Rodriguéz de Montalvo in an epic cycle of knights and nobility published some twenty years earlier. California (both the “island” Baja and, later, Alta California to the north) took the name from the epic’s Amazon queen Califía, beauteous of face, powerful of arm, noble of heart.

The following story takes place five and a half centuries after Califía’s story was written, and the irony is as cutting as the Amazon queen’s blade: “They kept only those few men whom they realized they needed for their race not to die out,” Rodriguéz de Montalvo writes. Little had he anticipated the rapid-fire series of plagues, wars, and environmental disasters that was to tip humankind into a downward spiral during the first century of the third millennium, slashing the world’s population to a fraction of what it had been at the year 2000, overturning social orders, turning dearly held beliefs and mores to dust overnight. Particularly he could not have predicted the propensity of one virus to attach itself to the male of the species, one generation after the next.

By the time of this story, the world holds one male human being for every ten or twelve females.

ONE

The Valley

On the right-hand side of the Indies there was an island called California, which was very close to the region of the Earthly Paradise.

**

(From The Labors of the Very Brave Knight Esplandían

by Garci Rodríguez de Montalvo,

translated by William Thomas Little)

DIAN

From a distance, there was nothing on the hillside, nothing but the dry grasses of late summer and a smattering of scrub bushes beneath the skeleton of a long-dead tree. From a distance, no unaided human eye could have picked out the dun and dusty figures from the grass around them; nonetheless, they were there, one long, slim human and two massive dogs. They had been on the hillside since morning, and they moved little.

Their presence had not gone completely undetected. An hour earlier a small herd of white-tailed deer quartering the hillside had abruptly cut short its graze to veer nervously away. Twice, sentinel quail settling into the arms of the twisted stump had alerted their flock to direct their attentions elsewhere. And now a turkey vulture appeared above the far side of the valley, gliding in languid circles on the updraft that rose off twenty acres of crumbling asphalt and debris, the remains of an office complex from Before. The bird spotted the three prone figures and sifted the wind through the distinctive fingers of her pinions, sidling across the currents to take a position a hundred feet above the invisible figures.

Hopeful thoughts flickered through her tiny brain and she dropped lower, then lower still, until one of the bodies jerked about to gnaw its flank, and another, the long one, turned its face to the sky and waved an arm. Faint avian disappointment came and went at these unmistakable signs of life, and the bird slid sideways toward the next valley. The three figures resumed their motionless watch.

Now, however, their stillness was one of alertness, even tension, rather than mere waiting. The human, no longer completely covered by the diminishing shadow of the grease bush, stared intently through a pair of large and ancient Artifact binoculars at the hillside ten miles away, where a faint haze of dust teased up from the ridge. In a few minutes the haze solidified into a cloud, its source coming clear: travelers. Eyes—blue human, yellow canine—focused on the spot, watching the drift of dust move down the face of the hill, saw the half-obscured wagons pause to weigh the temptation of the direct route through the Remnant against the unknown threats it could hide, saw the travelers turn to circle well clear of the tumbled remains. When the wagons had safely negotiated the dry streambed and regained the road, when it became clear that the travelers were firmly committed to the left-hand fork, the binoculars went into their case, the weapons were gathered up, and woman and dogs slithered over the top of the hill and disappeared.

JUDITH

Two hours later, near the place where the road’s left fork dwindled to its end, another woman watched for another small cloud of dust to rise against a backdrop of trees, chewing her lip with impatience. Her name was Judith, and she sat perched on the top step of a sprawling old farmhouse that had once been painted white, shelling dried beans. Her bare toes were drawn back from the hot edge of the sun on the next step down; the worn boards and pathway below were thick with beans that had missed the bowl under the sharp, irritable jerks of her work- hardened fingers.

Judith didn’t even see the waste she was making. Her eyes were on the Valley entrance, her inner gaze fixed on that vision of the morning’s frantic activity— no, call it what it was: panic, mindless and dangerous, that had gone on far, far too long. Bringing the Valley into line had been like pushing a laden cart uphill, and Judith ached with the strain. But at last the long-unused emergency drills were recalled, and order jerkily took hold, and finally the gears meshed and things ran smoothly: guards out, weapons ready, all metaphorical hatches securely battened.

Now there was nothing left to do but wait. Forty minutes earlier she had found herself standing alone on the veranda, wishing she had gone with Dian, wondering if she shouldn’t take a position at the Gates with a rifle, half-yearning for a return of the morning’s upheaval just so she’d have something to keep her occupied until she heard what she was thinking and berated herself: For God’s sake, you’re a lousy shot, Dian’s better off without you, and you should be grateful things finally calmed down. Go find something to do!

So she’d found a mindless task and settled to it—badly, with shameful waste—and waited for Dian.

The worst part was the silence. She felt smothered under it, this strange, thick stillness where there was usually the workaday noise of an active community—children shouting and adult voices raised in work and song, the rumble and thump of the mill machinery, the echo of hammer and the rasp of saw and the jingle of harnessed horses pulling plow or cart. The myriad sounds that made up the daily voice of the Valley were gone, the core of its life locked up and guarded in the hillside caves high above the farmhouse. The oddly muted sounds of cow and goat drifted down from the upper pastures; the cock crowed in protest from the enclosed run behind the barn. Even the imperturbable blue jay that haunted the walnut tree seemed flustered at the impact his raucous voice made on the still air and flew off into the redwoods. Judith listened to the few voices of low speech, the crackle and patter of the beans dropping into the basket, the breath soughing in and out through her nose: no competition for the pervasive quiet. The hot air shivered with silence, and Judith watched the Gates.

Not actual gates, of course, not like Meijing had— there was no way to wall the area against determined invaders, although God knew they’d talked about it, especially, Judith gathered, during the early years. But the Valley was peculiarly well suited for defense, the hills at its back steep and heavily wooded, the low ground in front marshy where the creek spread out between a pair of rocky prongs. And then, when the worst of the riots had been raging Outside, the community had responded to an unspoken urge to strengthen those prongs and built them higher and thicker until the Gates came into being. Nothing high explosives or a concerted effort wouldn’t push aside, but a few armed women atop the structure would slow an enemy down.

As now it seemed to be slowing Dian, damn it. The minutes crawled, beans continued to fall into the bowl and across the steps, and then finally, a faint suggestion of dust rising into the air down toward the Valley entrance. A minute later, sounds reached through the utter silence: a woman’s faraway voice—Dian’s, she was sure, calling a salute to her unseen sentries. In a minute Judith could hear the clear thud of cantering hooves on the planks of the lower bridge; her eyes shifted to the dam, the pond behind it as unnaturally motionless as the air without its usual midday complement of splashing bodies, the mill frozen against the weight of the collected waters. After four long minutes Dian appeared around the side of the mill, her horse at a trot. The smaller dog, a two-year-old brindle that stood thirty-four inches at the shoulder, shot away from her side to galumph like a mad ox through the shallow edges of the mill pond, heaving up great sheets of water at each stride until it stopped, belly-deep, to lap furiously. The other dog, fawn-colored and bigger by three inches and forty pounds, remained at Dian’s left stirrup until she turned her horse’s head to the water. Then he, too, waded forward to drink. Judith watched him closely for an indication of Dian’s feelings, and was relieved when he appeared relaxed enough to snap playfully at the water.

Dian only allowed her animals a small refreshment before pulling the horse back onto the road and whistling the dogs to her side. Judith heard hoof beats again as Dian crossed the mill bridge; as if the sound had been a signal, the rider shifted in the saddle to peer up at the house, then threw up an arm in greeting.

Judith started to rise, only to exclaim in exasperation both at the basket, which nearly upended down the steps, and at the awkwardness caused by her expanding belly. She thrust the beans to one side and stepped into the full sun to respond with a wide wave. In another moment Dian disappeared behind the apple orchard. Judith continued down the steps, pausing to bend laboriously and gather a few stray beans, then abandoned the project to set off across the stunted lawn to the entrance of the farmyard proper.

The ebook of Califia’s Daughters is currently $1.99 through Bookshop Santa Cruz, or Nook, or Kindle. If you prefer a signed paperback edition, Bookshop can get you one.