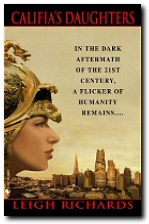

Califia’s Daughters (3): Dys- or Eutopia?

In the aftermath of a global catastrophe, how would the world settle down? Rural life would no doubt return to the fore—people need food before technology, any time. But given the kinds of machines, and the sorts of minds, we see in the 21stcentury, wouldn’t cities survive? More feudal in nature, perhaps, trading knowledge and technology for agricultural goods. And those on the edges, who are by their natures neither farmer nor city-dweller? Would not that woman be as frustrated by her world as her sister is today?

Califia’s Daughters (3)

By “Leigh Richards” (Laurie R. King )

TWO

. . . there were no males among them at all,

for their way of life was similar to that of the Amazons.

**

(From The Labors of the Very Brave Knight Esplandían

by Garci Rodríguez de Montalvo,

translated by William Thomas Little)

The two women who emerged from the black cavern of the barn door were a study in contrast. One was a tall, loose-limbed woman closing in on thirty, killing weapons tucked easily under her right arm, left hand stretched down as if making ghostly contact with some hip-level object. She was dressed in a long-sleeved shirt and long trousers over tall soft boots; everything about her was the color of dust. Her wiry, scorched-looking blond hair was closely cropped above angular cheekbones, sun-dark skin, and intensely blue eyes, and she walked with the lithe economy of a distance runner. Dian had chosen her name when she attained her womanhood, in a self- conscious but determined evocation of the goddesses of war and hunt, for, even then, half her lifetime ago, she had known what her skills would be. Her contributions of game to the village’s tables were regular, and she held a fanatic’s eye toward the security of their boundaries.

The woman at her side, the woman she called sister, was a full head shorter, looked more than her eight years older, and moved with the more compact strength of a person whose muscles dig and lift and build. Her face was browner than the sun could dye it and broad across the cheekbones, set with eyes of the darkest brown and surrounded by thick black hair, glossy smooth in the sun with glints of white in the braid down her back. Her mouth was soft and smiled easily, although there was a long history of burdens borne in the lines beside it. She wore a loose, sleeveless yellow blouse, amateurishly embroidered with bright flowers, and rough woven shorts belted with a similarly colorful and badly woven sash. She had simple, thin-soled sandals on her feet, and she walked with that pelvic looseness peculiar to the last weeks of pregnancy, when ligaments relax and the center of balance shifts almost daily.

The two women, in fact, shared no known ancestors. They were adoptive kin only, milk sisters, Dian rescued and brought to the Valley by the person they both had called “Mother.”

Judith was still smiling at Carmen’s truculent generosity when they reached the corner of the barn, and Dian made to turn right, toward her quarters up behind the building. Judith stopped her.

“Come to the house,” she suggested. “There’s some lemonade.”

“God, Jude, I would kill for lemonade. But I should go wash first—my clothes are filthy and there’s probably ticks in my hair.” The farmhouse, with its huge dining room and oversize kitchen, was the social and (if the word can be stretched to fit a community of 285 souls) political center of the Valley, as well as its lending library, town hall, records office, and savings bank. However, it was also Judith’s home, and Judith was considerably more fastidious than Dian in matters of housekeeping.

“Don’t worry about it,” she replied, but added, “we’ll sit on the porch.”

They went around to the front, up the worn steps where Judith had shelled the beans, Dian raising an eyebrow at the mess but refraining from comment. Judith scooped up the basket and bowl and pulled open the much-mended screen door, then continued through into the house while Dian leaned her things against the screen walls, her left hand unconsciously signaling to absent dogs that they should lie down, and eased herself into one of the shabbier chairs. She let out a deep breath at this first moment of peace she’d had in what had already been a long day and was far from over; then she put first one booted foot up on the low table, crossed the other over it, and closed her eyes.

Only to become suddenly aware of how very angry she was.

In an unknowing echo of Judith’s earlier vision, the picture her sister had painted stood vivid behind Dian’s eyelids: the Valley’s residents racing round like frightened chickens, as open to invasion as a group of twentieth-century innocents. It made her feel like hitting something. She wanted to go out and shake Laine until the woman’s teeth rattled—she was supposed to be Dian’s second; why hadn’t the damned woman just taken charge? Judith shouldn’t have to do it all, she wasn’t in any condition to carry that burden. Hell, Judith really shouldn’t be here at all, she should be up at the caves with Kirsten and the others.

But it wasn’t just Laine she was furious with, wasn’t even stubborn Judith. You stupid, stupid bitch, she swore at herself. You think you can go and have a camp-out any time you feel bored? What if you’d gone toward the sea like you wanted to? What if you hadn’t just happened to wake up so early, hadn’t had that headache, had gone downhill for firewood instead of up?

Christ, you could have been counting waves and contemplating your fucking navel while the whole Valley was being wiped out. You’d have come back and found burnt-out ruins and the buzzards picking over their bones, and how about boredom then?

Hey, a small voice objected, if I hadn’t been bored and gone out in the first place, we wouldn’t have known the wagons were coming until the outer guards spotted them, and we’d be in no better a spot. But she rode over her mind’s objection, because she was frightened and furious and grave danger was coming wrapped inside two strange wagons, and there was not a thing she could do to stop it.

Luck alone had put her on that hillside at that time. She’d been bored because nothing had happened for so long, and now that something was happening, she wasn’t ready. Of all the stupid, irresponsible things, to be off in the woods playing with the dogs instead of doing the job the entire Valley depended on her for. Only dumb, blind, terrifying luck had prevented those wagons from rolling into the Valley unannounced.

Dian was all too aware of the outsize role played by luck in the Valley’s very existence: luck the place was overlooked by roving bands of Destroyers at the beginning, two generations ago; luck those raiders thirty years ago hadn’t been better armed or more numerous; luck the people hadn’t just quietly starved to death or fallen under some plague; luck they hadn’t been twisted into brutal parodies of humanity like so many other communities. They were even fortunate in their fairly high fertility rate, and two of the boy children born in the last three years looked as if they might, please God, survive. Luck, too, in her own life: what but sheer chance could have brought the woman she came to call Mother to the crossroads just a few hours after a girl baby, not yet walking, had been abandoned? Sweat, and some blood, and more than a few tears had played their parts, but the potential catastrophes kept her sleepless as it was—and now her irresponsible inattention to the job had placed the Valley in jeopardy, dependent yet again on the whims of luck.

She gnawed a bit of rough skin from her knuckle and opened her eyes to the rich fields and the orchards beyond, to the smooth pond and the lush hillside vineyard and, rising dark above the far orchard, the protective curve of hills, clothed in silent redwoods. A pulse of some series of emotions seized her, something that for an instant brought her absurdly close to tears: love for those hills, that orchard; despair that she couldn’t seem to be happy within those bounds like Judith; knowledge that somewhere—hidden deep, faintly felt, instantly suppressed, but nonetheless there—had been a tiny wistfulness at the idea of being free of the Valley, that finding the vultures squabbling over their bones would have been a horror but also (don’t even think it!) a freedom.

Alone was a word with two edges.

The gentle sound of ice chips moving against delicate glassware broke her bitter reverie, startled her with a brief but vivid evocation of a string of naming ceremonies: Mother, Judith . . .

But it was only Judith, backing through the inner door, holding a laden tray with solemn attention.

“Both ice and the glasses?” Dian asked. “I don’t know that the day calls for a celebration, Jude.” Ice marked a social occasion, since the supply was limited to what one small freezer in the healer’s office could produce and what the Valley had managed to store in the deep cave under sawdust. The glasses holding the ice were quite simply irreplaceable.

Judith set the tray on the table and lowered her bulk into the chair next to Dian’s. She handed Dian a glass and held her own up to the light to admire the pale color of the liquid and the translucent slice of lemon, running her tongue voluptuously over the smooth edge before she drank deeply. She set the glass down with care on the table.

“I find them a comfort. Sometimes I get one out just to have a drink of water. It’s like I can feel Mother’s hands on them. And Father’s too.” Judith’s father had died before his daughter entered womanhood, so that Dian had only a vague memory of him: neatly trimmed beard, strong arms, happy voice. One of his sons had lived, the pride of the community, Judith’s big brother, Peter—hidden away in the cave now with the others. “I’ve gone ahead with the preparations we talked about. The sentries are set, the next ones should go out in about an hour; that’s what Jeri said you wanted. I decided that you were right about wanting to keep the visitors away from the houses, but keeping them outside the Gates entirely seemed too blatant a message. They’re hardly concealing themselves, after all. So I set Hanna and her family to putting up tables outside the slaughtering sheds, asked her to heat up the boilers. Did everything seem to be coming along okay when you rode by?”

Dian nodded. “Yes, it looked fine. I still think outside the Gates would be better, but even in the meadow I can put Laine and Jeri in the trees with their rifles, to cover us. What did you decide about Ling?”

“Dian, I can’t send our healer up to the caves when there might be trouble.”

“‘Trouble,’” Dian snorted.

“For heaven’s sake, she’s been here ten years, plenty long enough to knock the aristocratic edges off her. And she never was as fragile as she looks.”

“That’s true,” Dian admitted. The healer’s delicate hands had never hesitated in that emergency amputation last year; her lovely Chinese eyes had not so much as winced away from the sight of the Smithy’s bloodbath. The woman was an enigma—no family, no casual relationships, no reason to be here, as far as Dian could see. She’d just ridden in with Mother from a trip to Meijing nine and a half years ago and been here ever since. She’d come here to leave something behind, no doubt. Or someone.

Dian shook her head to clear out the extraneous thoughts and tapped the last precious chips of ice into her mouth, placing the glass on the tray with care. “I’d better go feed the dogs,” she said, then paused in the act of getting to her feet. “Speaking of whom, how many of them do you think I should have down there tonight? I’m not sure I can control more than four at once if things go bad. I’d have to just turn them loose.”

Judith looked at her grimly. “If things go bad, we’d want them turned loose. Bring five or six. You won’t have any trouble with that many if things stay friendly.”

“Right.” Dian raked her long fingers back and forth through her hair, loosing a shower of dried leaves and dust. “Look, you asked me this morning if I thought there was danger. I don’t know, but it doesn’t feel exactly dangerous.” Her hand moved to the back of her neck, and she stood, cupping the spot. “I wish I could pin it down, but it just feels like something very odd is going on. On the surface this whole thing is a straightforward problem, but I feel . . . prickly. And it’s not just the foxtails in my shirt either!” She shot a glance at Judith, then sighed, gathered her weapons, and went out. Judith sat and looked at the sparkling, empty lake, her hands unconsciously traveling up and around the swollen globe of her belly.

The sun moved across the sky, the shadows began to lengthen. In the chapel, Judith recited the prayers she had learned at her mother’s knee, then sat listening to the polyglot prayers of those around her, from Latin Hail Marys to half-remembered Nicene Creeds: the age-old divisions between Catholic and Protestant meant about as much now as the division between MacCauley, the Valley’s nominal owners, and Escobar, who had begun as farm hands. Judith was both, as her prayers were both Catholic and Protestant. In the infirmary, Ling the healer finished packing up her scanty drugs, set another batch of bandages to sterilize, and lit a stick of incense in front of her small Buddhist altar, praying in fervent Chinese that her services would not be needed. In the barn, Carmen, speaking her own native Spanish, reciting her own form of prayer, talked to her equine charges, telling them what was going on and that they shouldn’t worry, before she went to help her two co-wives with an early milking.

Not all the residents prayed. Dian finished doctoring the paw of the young bitch, Maggie, who had limped home during the afternoon, then went to look for Laine and Jeri. She found her two lieutenants arguing over sniper positions among the trees and buildings, and settled it by telling them who she wanted where. Before Laine could do more than bristle, a rider cantered up the road with news of the wagons’ progress; she hesitated between Laine and Dian, then to Dian’s further vexation, gave her report to the space between them. The report was brief; the rider’s relief at getting away from the two aggrieved women palpable.

Others prepared for the coming invasion in a manner neither spiritual nor combative but merely practical. In the clear space between the sheds atop which two snipers would lie, plank tables were being assembled, cook fires lit, beer barrels hauled, slabs of beef laid ready, mountains of corn shucked.

Of all the residents of the Valley, perhaps only one nurtured a degree of satisfaction: Judith’s thirteen year-old daughter, Susanna, although as apprehensive as anyone else, was also gratified that she had been allowed to stay in the Valley instead of being hidden away with the men and the children. She pestered Dian until finally her aunt threatened to throw her bodily into the pond and sent her down to help at the makeshift kitchen.

And in the big cave, hidden deep in the hillside over the Valley, more prayers were said, another set of defense preparations was made, and old Kirsten prepared to tell one of her simple stories of Before.

The ebook of Califia’s Daughters is currently $1.99 through Bookshop Santa Cruz and Nook and Kindle. Or if you prefer a paperback, Bookshop can get you one of those.

I wonder where Meijing is located? Is it San Francisco? How much technology survives in the cities?

Yes, it’s SF. (The name would translate “beautiful city”)

I’d guess a fair amount of tech would survive, but little new stuff would be manufactured, or developed.

L.